What is Cash Flow? Complete Business Financial Analysis Guide 2026

Table of Contents

Cash Flow Definition and Business Importance

Cash Flow Statement: Structure and Regulatory Requirements

Operating Cash Flow: Core Business Performance Measure

Investing Cash Flow: Funding Business Growth

Financing Cash Flow: Capital Structure Management

Free Cash Flow: Money Available for Growth and Returns

Cash Flow Analysis Ratios and Metrics

Discounted Cash Flow: Investment Valuation Applications

Cash Flow Forecasting and Financial Planning

Cash Flow Management Strategies for Business Success

Real-World Example: Walmart Cash Flow Analysis

Warning Signs: When Cash Flow Indicates Problems

Conclusion: Using Cash Flow Analysis for Better Business Decisions

Frequently Asked Questions About Cash Flow

Cash flow represents the lifeblood of any business. It's the movement of money into and out of a company during a specific period, measured through three distinct categories. Understanding what cash flow is becomes crucial for anyone analyzing business financial health, whether you're an investor evaluating stock opportunities or a manager making strategic decisions about operational efficiency and growth investments. Knowing what cash flow is and how it operates distinguishes successful financial analysts from those who rely solely on profit metrics. Without adequate cash flow, even the most innovative business models ultimately fail to survive market challenges and competitive pressures.

Cash Flow Definition and Business Importance

Cash flow measures actual money movement through your business over a specific time period. Unlike accounting profits that include non-cash items and accrual-based adjustments, cash flow tracks real dollars changing hands between the business and external parties. This fundamental difference makes cash flow analysis essential for assessing true financial health and operational sustainability. Businesses can appear profitable on paper while simultaneously facing dangerous liquidity crises that threaten their very existence.

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) mandated standardized cash flow reporting in 1987, recognizing that balance sheets and income statements alone couldn't tell the complete financial story. This regulatory framework transformed financial analysis by providing consistent, comparable data across all public companies. Before this mandate, investors struggled to compare companies using different reporting standards and definitions, creating substantial analytical challenges and investment risks.

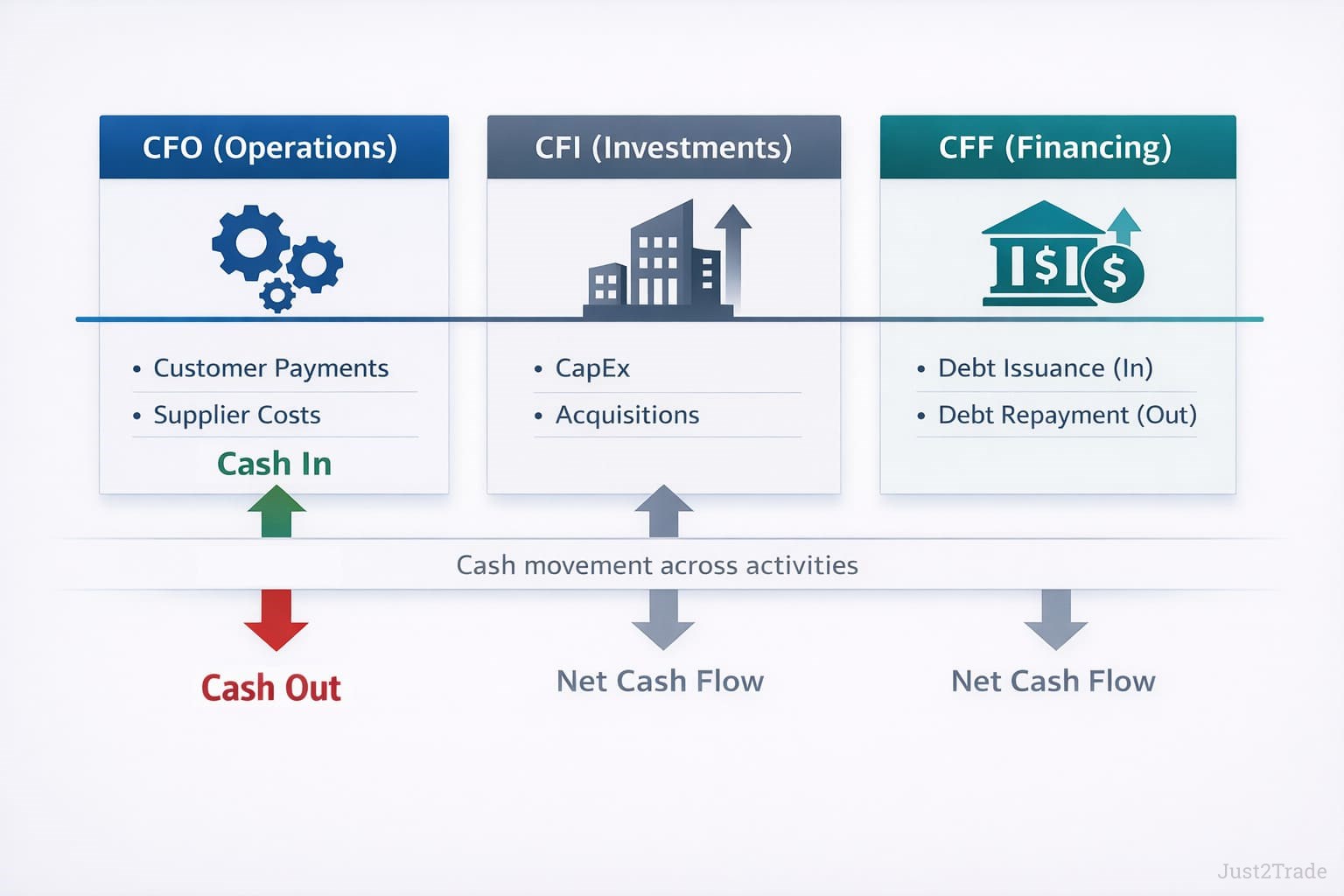

Every dollar flowing through a business falls into one of three categories that together paint a comprehensive financial picture:

- Operating Cash Flow (CFO) – Cash generated from core business activities including sales revenue collection and operating expense payments

- Investing Cash Flow (CFI) – Cash used for long-term growth investments in property, equipment, acquisitions, and strategic assets

- Financing Cash Flow (CFF) – Cash movements from capital structure activities including debt issuance, equity offerings, and shareholder distributions

These three categories work together as an integrated system. They create a comprehensive picture of how a company generates cash from operations, where it strategically invests for future growth, and how it manages critical relationships with investors and creditors. Understanding the interplay between these categories reveals management's strategic priorities and financial discipline.

Why Cash Flow Matters More Than Profit

Profitable companies can still fail. How does this happen? They run out of actual cash to meet obligations. Net income includes non-cash charges like depreciation, amortization, and accrued revenues that haven't been collected yet. A company might show $5 million in accounting profit while actual cash balances decrease due to working capital absorption or capital investments. This paradox has destroyed countless businesses that looked healthy on income statements but lacked actual liquidity to pay employees, suppliers, or creditors.

Cash flow reveals critical timing differences that profit masks. When a business builds inventory ahead of seasonal demand or extends generous payment terms to win customers, working capital absorbs substantial cash even as the income statement shows impressive profits. This disconnect can create dangerous situations where profitable companies face liquidity crises. The timing mismatch between revenue recognition and actual cash collection often catches inexperienced managers by surprise during rapid growth phases. Revenue gets recorded when goods ship, but cash arrives weeks or months later – meanwhile, suppliers and employees demand immediate payment.

The cash flow to net income ratio should ideally approach 1:1 for mature businesses. Significant persistent deviations signal potential earnings quality concerns requiring immediate investigation by analysts and management. Ratios consistently below 0.8 suggest aggressive revenue recognition, deteriorating collections, or unsustainable working capital practices. Understanding what cash flow is relative to reported profits helps investors identify accounting manipulation and assess true business performance.

Net Cash Flow: Total Cash Movement Analysis

Net cash flow represents the total change in cash position during a specific period. It's calculated by summing all three cash flow categories:

Net Cash Flow = Operating Cash Flow + Investing Cash Flow + Financing Cash Flow

This comprehensive measure shows whether a company's total cash increased or decreased. Positive net cash flow indicates cash balances grew during the period – the company generated or raised more cash than it spent. Negative net cash flow shows cash balances declined as cash outflows exceeded inflows.

Both positive and negative net cash flow can be healthy depending on strategic context. A growing company might show negative net cash flow while investing heavily in expansion, funded by strong operations and strategic financing. Conversely, a struggling company might temporarily show positive net cash flow by liquidating assets or securing emergency loans – not sustainable long-term.

Analysts examine net cash flow trends across multiple periods to identify patterns. Consistent negative net cash flow raises concerns about sustainability. However, short-term negative movements often reflect strategic investments positioning companies for future growth and competitive advantage.

Cash Flow Statement: Structure and Regulatory Requirements

The cash flow statement reconciles cash movements with other financial statements, creating a complete picture of financial performance. FASB Statement No. 95, issued in November 1987 and effective for fiscal years ending after July 15, 1988, established comprehensive standardized reporting requirements for all public companies. This regulatory framework ensures investors receive consistent, comparable information across industries and time periods. The standardization revolutionized financial analysis by eliminating the confusion that previously plagued cross-company comparisons.

Before the 1987 FASB mandate, companies used various inconsistent "funds flow" definitions. Some focused on working capital changes, others emphasized cash and short-term investments, while still others used entirely different approaches. This diversity created substantial confusion and severely limited meaningful comparability across companies, hampering investment analysis and decision-making. Investors essentially needed to learn different "languages" to understand different companies' financial statements, creating massive inefficiencies in capital markets and increasing information asymmetry between companies and investors. The FASB Statement 95 implementation standardized these practices across all public companies.

FASB Requirements and Professional Standards

The Financial Accounting Standards Board serves as the primary accounting standards setter for public companies operating in the United States. Since implementing the 1987 cash flow mandate, FASB has continually refined reporting requirements through subsequent updates and clarifications based on evolving business practices and analytical needs. These refinements address emerging issues like classification of specific transactions and disclosure requirements for complex financial instruments.

Professional analysts use CFA Institute financial analysis frameworks when evaluating cash flow statements for investment decisions. These rigorous frameworks emphasize understanding the quality of earnings, sustainability of cash generation patterns, and complex relationships between different cash flow categories. The standardized FASB format enables meaningful comparisons across diverse industries and extended time periods. Analysts can quickly identify unusual patterns, benchmark performance against peers, and assess whether reported earnings translate into actual cash generation – the ultimate test of business quality.

Operating Cash Flow: Core Business Performance Measure

Operating cash flow (OCF) represents the primary indicator of fundamental business sustainability and operational efficiency. It measures cash generated directly from core business activities – selling products or services, collecting payments from customers, and paying suppliers and employees for operating expenses. Think of OCF as the essential cash engine that keeps daily operations running smoothly without requiring external financing. Strong OCF demonstrates that a company's basic business model works effectively in converting sales into actual available cash.

The calculation methodology starts with net income from the income statement, then systematically adjusts for non-cash items and working capital changes that affect the timing of cash movements. Companies can use either the direct method showing actual cash receipts and payments or the indirect method adjusting net income. Most companies strongly prefer the indirect method for its computational simplicity and clearer connection to the income statement. The indirect method also helps analysts understand exactly which non-cash items and working capital changes drive differences between reported profits and actual cash generation.

According to financial analysis research published in MDPI, cash flow ratios consistently provide superior predictive power compared to traditional accounting ratios when assessing future financial performance and bankruptcy risk. Operating cash flow serves as the critical foundation for these advanced analyses. Research demonstrates that cash flow-based indicators, particularly operating cash flow and cash flow-to-debt ratios, serve as more reliable early warning signals of financial distress than profit-based metrics alone, giving stakeholders crucial advance warning of potential problems before they become critical.

Calculating and Interpreting Operating Cash Flow

The indirect method formula works through this systematic process:

Operating Cash Flow = Net Income + Non-Cash Expenses – Increase in Working Capital

Non-cash expenses primarily include depreciation of physical assets and amortization of intangible assets. These reduce reported net income without any corresponding cash outflow. Working capital changes meticulously track movements in accounts receivable from customer credit, inventory investments, and accounts payable to suppliers.

Strong positive OCF indicates a company generates sufficient cash from core operations to sustain itself independently without relying on external financing or asset sales. Negative OCF raises legitimate concerns, though proper context always matters significantly. A rapidly growing company might display temporary negative OCF as it invests heavily in inventory buildup and extends credit terms to capture new customers during expansion phases. The key distinction lies between temporary strategic negative OCF and chronic operational problems.

Investing Cash Flow: Funding Business Growth

Investing cash flow (CFI) comprehensively tracks money spent on long-term assets and strategic investments that drive future growth. Property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) purchases represent the largest and most visible component in most industries. Business acquisitions, research and development infrastructure spending, and purchases of investment securities also appear prominently in this category. These investments typically consume substantial cash today with the expectation of generating returns over many future years.

Growing, healthy businesses typically show consistently negative investing cash flow over extended periods. They're strategically spending cash today to build operational capacity and competitive advantages for sustainable future growth. This isn't necessarily concerning – it signals active strategic investment in long-term competitiveness rather than stagnation or decline. Companies that stop investing adequately in CFI often see market share erode as competitors outspend them on technology, capacity, and innovation.

The critical analytical question becomes whether these substantial investments will generate sufficient future cash returns to justify today's capital allocation decisions. Smart analysts examine the relationship between CFI spending and subsequent OCF growth to assess management's capital allocation effectiveness.

Understanding Negative Investing Cash Flow

Consider these contrasting real-world scenarios that illustrate proper CFI interpretation:

- Scenario A: A thriving manufacturing company spends $50 million on state-of-the-art production facilities and automation equipment. Investing cash flow shows -$50 million for the period. This substantial outflow represents strategic expansion positioning for increased future capacity and efficiency. The company expects these investments to reduce operating costs by 20% and increase production capacity by 40% over three years, generating strong returns on invested capital.

- Scenario B: A struggling regional retailer facing competitive pressure liquidates underperforming stores and sells excess equipment at discount prices. Investing cash flow shows +$30 million from asset sales. This positive CFI might actually indicate serious financial distress and strategic retreat rather than strength. The company is essentially converting long-term assets into short-term cash to fund operations – a pattern that cannot continue indefinitely.

Negative CFI frequently signals healthy, confident growth investment. Consistently positive CFI over multiple years might suggest either lack of attractive investment opportunities or concerning asset liquidation to generate desperately needed cash. Analysts examine both the absolute level and directional trends in CFI to understand management's strategic confidence and capital allocation philosophy.

Financing Cash Flow: Capital Structure Management

Financing cash flow (CFF) reveals precisely how a company manages complex relationships with its capital providers – both equity investors and debt creditors. This critical category captures all cash movements related to the company's capital structure and includes several major transaction types:

- Stock issuances to raise equity capital (cash inflow)

- Share buyback programs returning capital (cash outflow)

- New debt borrowing from banks or bond markets (cash inflow)

- Scheduled debt repayment and refinancing (cash outflow)

- Regular dividend payments to shareholders (cash outflow)

Positive CFF indicates a company is actively raising more capital than it's returning to investors. Negative CFF demonstrates the company is confidently returning substantial money to shareholders through dividends and buybacks or strategically paying down debt to reduce leverage. Neither pattern is inherently good or bad – proper context and strategic rationale determine whether the capital allocation strategy makes sound financial sense. The optimal financing strategy varies dramatically based on growth stage, industry characteristics, and competitive dynamics.

Mature, stable companies with predictable cash generation often show persistently negative CFF as they systematically return excess cash to shareholders who can redeploy it elsewhere. High-growth companies in expansion mode typically show positive CFF as they raise capital from multiple sources for aggressive growth investments. Technology startups frequently show large positive CFF from venture capital rounds, while established dividend aristocrats consistently show negative CFF from regular quarterly distributions.

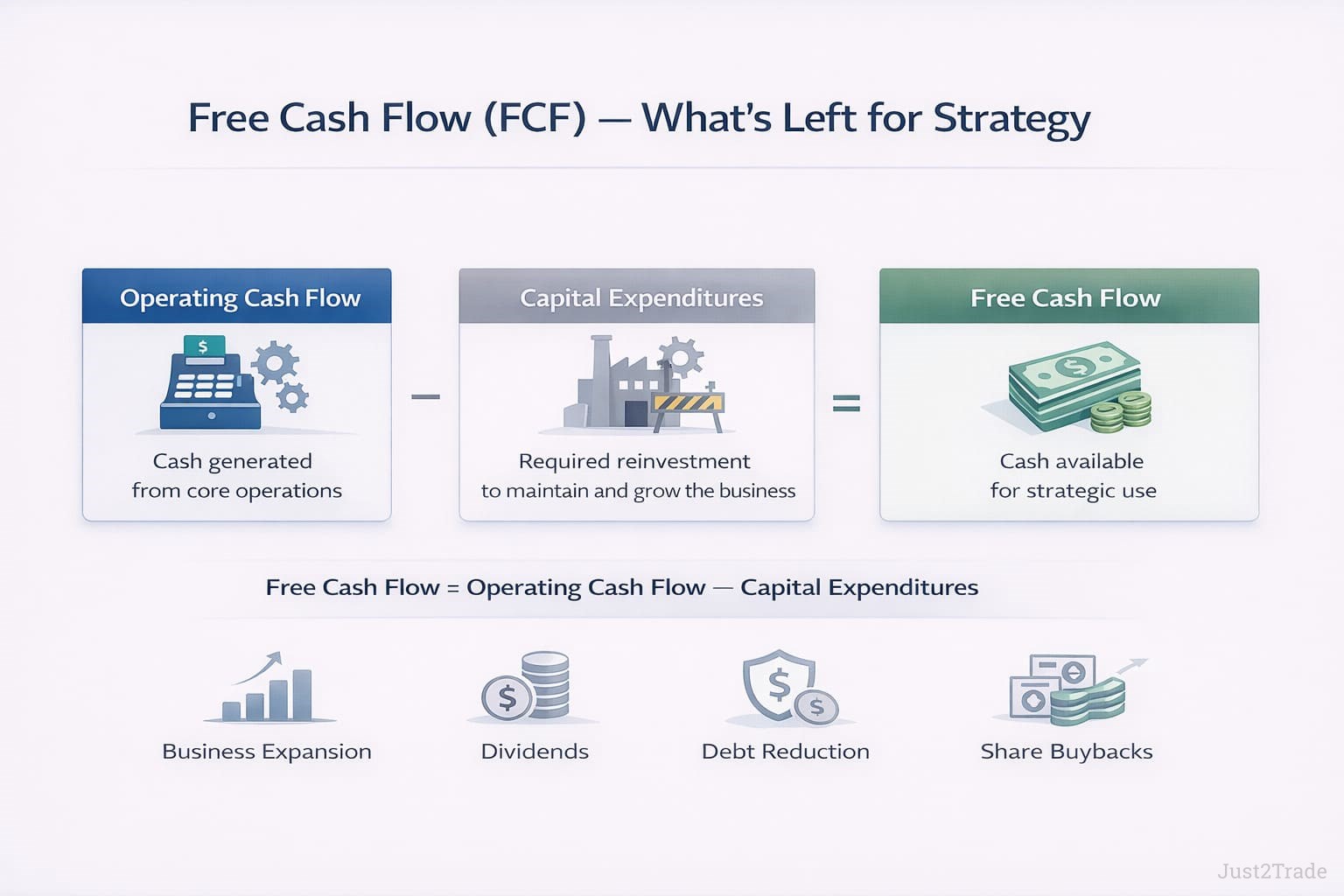

Free Cash Flow: Money Available for Growth and Returns

Free cash flow (FCF) represents the discretionary cash available after maintaining existing operations and funding necessary growth investments. It's calculated with this straightforward but powerful formula:

Free Cash Flow = Operating Cash Flow – Capital Expenditures

This elegant metric matters tremendously for rigorous valuation analysis. Investment analysis frameworks from CFI consistently emphasize FCF because it directly shows money genuinely available for four critical strategic uses:

- Organic business expansion and strategic growth investments

- Regular dividend payments providing income to shareholders

- Aggressive debt reduction and balance sheet deleveraging

- Share buyback programs increasing per-share shareholder value

Companies with consistently strong positive free cash flow enjoy tremendous strategic flexibility and financial strength. They can weather economic downturns, pursue opportunistic acquisitions, and reward shareholders without jeopardizing operational stability.

Levered vs Unlevered Free Cash Flow

Sophisticated analysts carefully distinguish between two important FCF variations with different analytical purposes. Levered free cash flow (LFCF) includes the full effects of debt financing – mandatory interest payments reduce cash available to equity shareholders. Unlevered free cash flow (UFCF) deliberately excludes all debt effects, showing pure cash generation capacity before any financing decisions.

UFCF enables fundamentally fair comparisons between companies with dramatically different capital structures. A company carrying heavy debt might show substantially lower levered FCF due to large interest payments, yet demonstrate similar unlevered FCF to a debt-free competitor. This important distinction reveals true operational efficiency independent of management's financing choices. Private equity firms particularly focus on UFCF when evaluating acquisition targets, as they can optimize capital structure post-acquisition regardless of the seller's previous financing decisions. Comparing LFCF to UFCF also reveals how much financial leverage costs the company in terms of cash availability for growth investments or shareholder distributions.

Cash Flow Analysis Ratios and Metrics

Professional financial analysts systematically employ several key ratios to rigorously assess cash flow quality and overall financial health. These sophisticated metrics provide substantially deeper insights than examining raw cash flow numbers alone without proper context. Ratios enable meaningful comparisons across companies of different sizes, industries, and business models – turning absolute dollar amounts into relative performance indicators that reveal underlying financial strength or weakness.

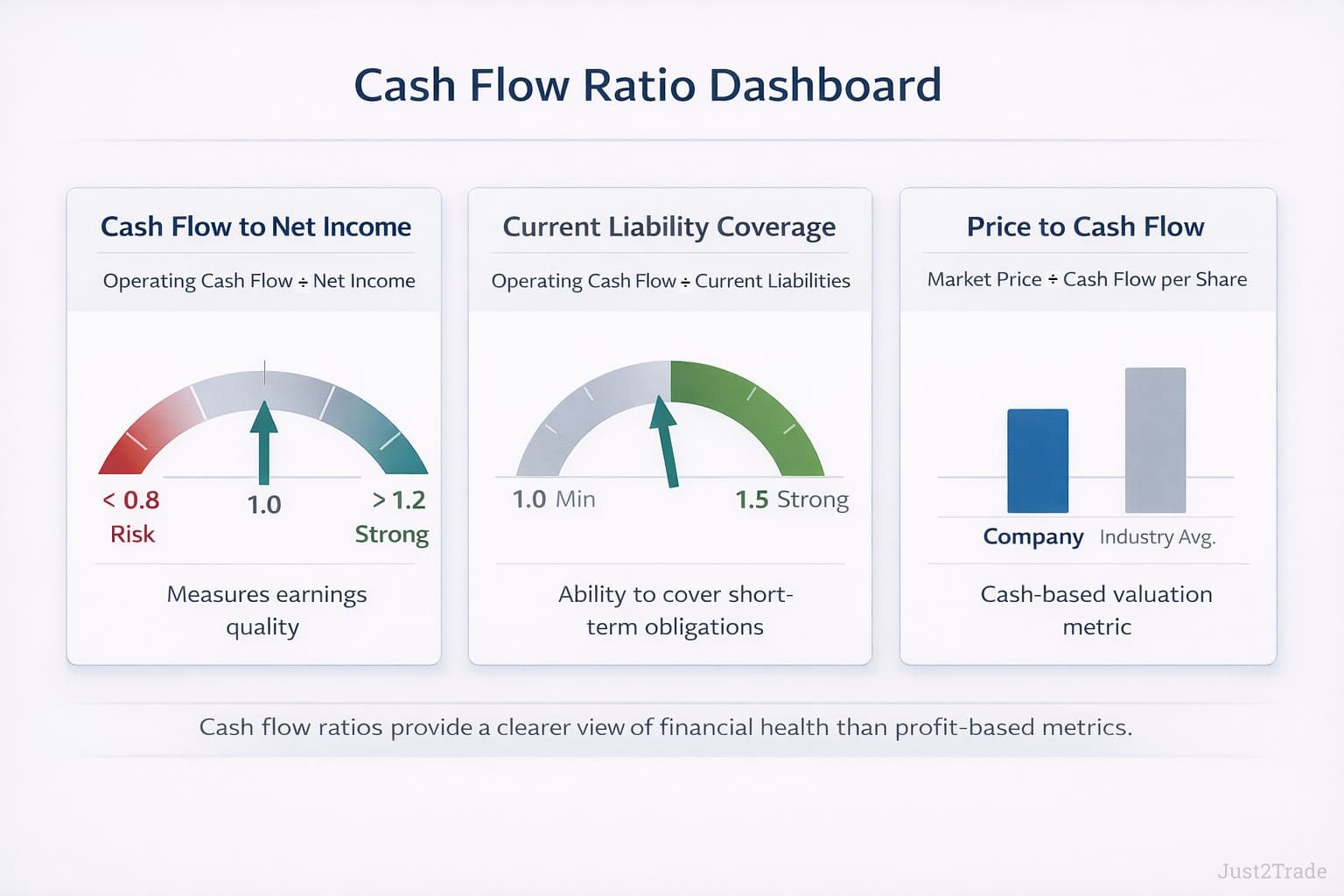

Key Cash Flow Ratios for Financial Analysis

1. Cash Flow to Net Income Ratio

Formula: Operating Cash Flow ÷ Net Income

Neutral/Acceptable range: 0.8 to 1.2 per financial analysis standards

Strong performance: Above 1.2

Warning threshold: Below 0.8

This critical ratio directly measures fundamental earnings quality. Values in the 0.8 to 1.2 range indicate acceptable earnings quality where reported profits are reasonably supported by cash generation. Values consistently above 1.2 suggest genuinely high-quality earnings with strong cash conversion efficiency – the company is collecting cash faster than it's recognizing revenue, often indicating strong competitive positions and customer demand. Values persistently below 0.8 raise serious concerns about potentially aggressive accounting practices or steadily deteriorating working capital management.

2. Current Liability Coverage Ratio

Formula: Operating Cash Flow ÷ Current Liabilities

Strong benchmark: Above 1.0 per industry standards

Excellent performance: Above 1.5

This essential liquidity metric clearly indicates whether normal operations generate sufficient cash to comfortably cover all short-term obligations. A ratio above 1.0 means the company generates enough operating cash flow to cover its current liabilities at least once over. Ratios below 1.0 may indicate potential liquidity problems, signaling that the company may need to rely on additional financing or asset sales to cover its short-term obligations. During economic downturns or industry stress periods, companies with ratios above 1.5 typically maintain access to credit markets while weaker competitors face funding challenges.

Price to Cash Flow Ratio

Formula: Market Price per Share ÷ Operating Cash Flow per Share

Typical range: 10-20 for mature companies per valuation standards

Value opportunity: Below industry average

This widely-used valuation metric often proves considerably more reliable than traditional P/E ratios because directly manipulating cash flow is substantially harder than adjusting reported accounting earnings through various discretionary choices. Lower P/CF ratios relative to industry peers might indicate attractive undervaluation opportunities deserving deeper investigation.

Discounted Cash Flow: Investment Valuation Applications

Discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis represents the gold standard methodology for valuing investments based on rigorous projections of future cash flows. The theoretical foundation recognizes that money received today is inherently worth more than the identical amount received in the future – the fundamental time value of money principle that underlies all modern finance. A dollar today can be invested to earn returns, making it more valuable than a dollar arriving years later.

DCF valuation works systematically through these critical steps:

- Project detailed future cash flows for an explicit forecast period of 5-10 years

- Estimate a terminal value capturing all cash flows beyond the forecast period

- Discount all future cash flows to present value using the weighted average cost of capital (WACC)

- Sum all present values to determine total intrinsic business value today

While theoretically powerful and widely used, DCF analysis relies fundamentally on subjective assumptions. Small changes in projected growth rates or discount rates can dramatically alter calculated valuations by 30% or more. This sensitivity requires analysts to conduct thorough scenario analysis and sensitivity testing before making investment decisions based on DCF results. A 1% change in the discount rate might swing valuation by hundreds of millions of dollars for large companies. Professional analysts typically model three scenarios – optimistic, base case, and pessimistic – to understand the range of possible intrinsic values rather than relying on a single point estimate.

Cash Flow Forecasting and Financial Planning

Cash flow forecasting provides essential forward-looking visibility into future liquidity positions and funding needs. This critical planning tool enables proactive management decisions rather than reactive crisis responses when cash shortages unexpectedly emerge. Forecasting transforms cash management from firefighting to strategic financial resource planning. Grasping what cash flow is in future periods allows companies to secure financing before crises develop rather than scrambling for emergency funding.

Effective forecasting combines several complementary approaches:

- Direct method projections estimate specific cash receipts from customers and payments to suppliers based on detailed operational plans

- Indirect method forecasts start with projected net income and adjust systematically for anticipated timing differences

- Scenario analysis models best-case, worst-case, and most-likely outcomes to understand potential range

Companies should update cash flow forecasts monthly at minimum, weekly during growth phases or tight liquidity periods. This disciplined approach identifies emerging problems early when corrective actions remain feasible and relatively painless. Businesses that forecast proactively rarely face unexpected cash crises, while those that ignore forecasting often encounter devastating surprises. Rolling 13-week cash flow forecasts have become industry standard for companies facing liquidity challenges, providing granular visibility into near-term cash needs while maintaining longer-term perspective.

Cash Flow Management Strategies for Business Success

Effective cash flow management fundamentally separates thriving businesses from those struggling merely to survive quarter-to-quarter. Smart managers systematically focus on three interconnected strategic areas that collectively optimize cash generation and utilization:

- Working Capital Optimization requires balanced attention across all components. Accelerate accounts receivable collection through prompt professional invoicing and attractive early payment incentives. Optimize inventory levels carefully balancing customer service expectations against cash efficiency imperatives. Extend accounts payable strategically without damaging critical supplier relationships.

- Cash Conversion Cycle Improvement measures precisely how quickly a business converts investments in inventory and receivables back into available cash. Shorter cycles mean substantially faster cash generation and dramatically reduced expensive financing needs. Best-in-class companies continuously benchmark their cash conversion cycles against industry leaders, identifying specific improvement opportunities in each component.

Improving Cash Flow Through Working Capital Management

Working capital management directly impacts cash flow through several high-leverage areas. Accounts receivable management focuses on credit policies, invoicing speed, and collection procedures. Tighter policies generate faster cash but might cost sales.

Inventory management balances competing demands. Too much inventory absorbs cash unnecessarily. Too little risks stockouts losing customers. Sophisticated companies use data analytics identifying optimal levels by product category.

Accounts payable timing strategically uses supplier credit as essentially free short-term financing. Pay on the last day terms allow without incurring late fees or damaging relationships. This simple discipline preserves cash for other uses.

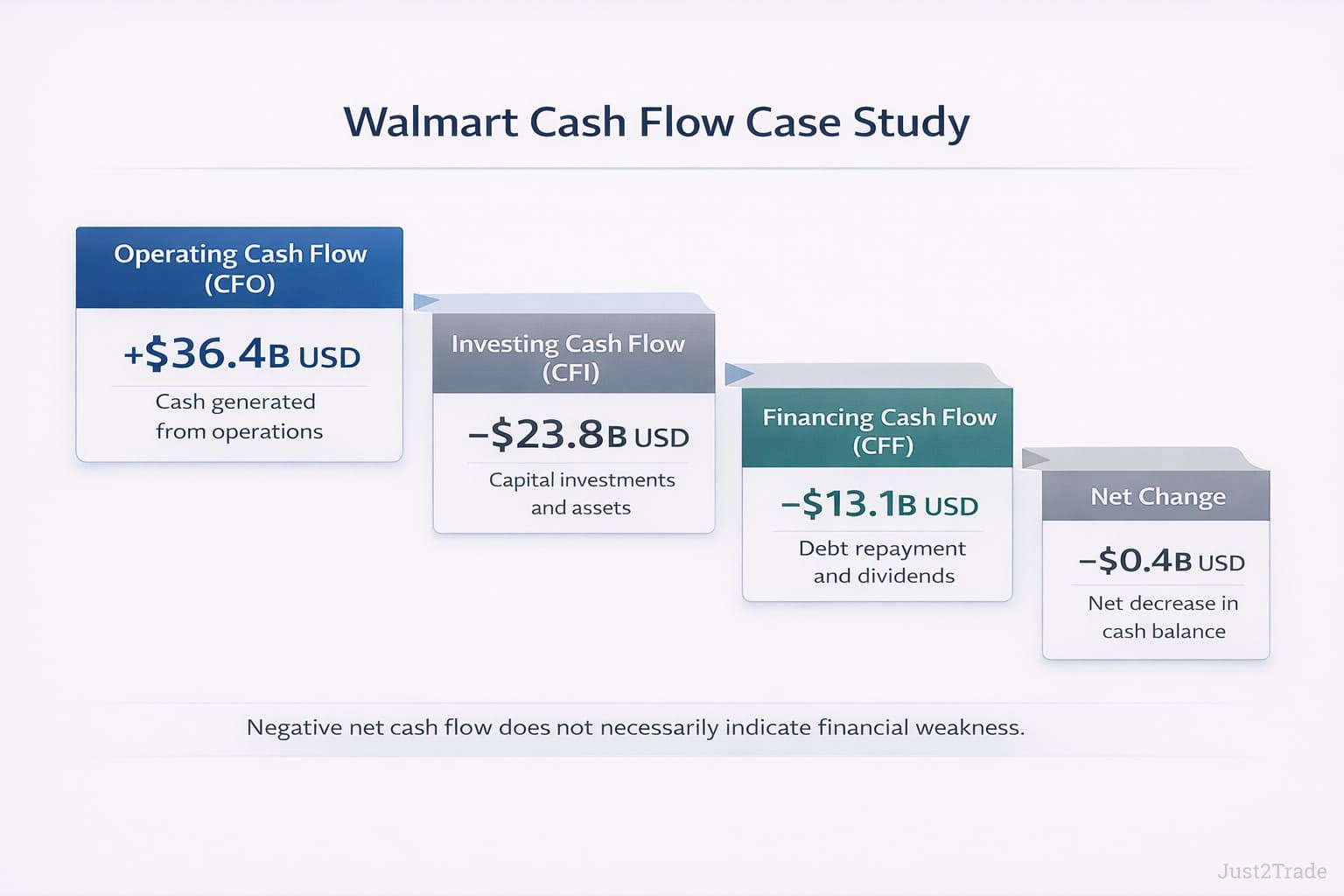

Real-World Example: Walmart Cash Flow Analysis

Looking at Walmart's actual financial statements clearly illustrates these concepts in practical action. For fiscal year 2025, Walmart reported the following cash flow performance:

- Operating Cash Flow: $36.4 billion (up 2.0% from prior year)

- Investing Cash Flow: -$23.8 billion (primarily property and equipment investments)

- Financing Cash Flow: -$13.1 billion (debt repayment and shareholder dividends)

- Net Cash Change: -$0.4 billion

This characteristic pattern reveals a mature, financially stable business executing a balanced strategy. Walmart generates truly substantial cash from massive retail operations, invests heavily and consistently in store improvements and technology infrastructure, and systematically returns significant excess cash to shareholders through reliable dividends while maintaining a conservatively strong balance sheet. The slight net cash decrease doesn't signal problems – it shows disciplined capital allocation where the company invests in growth and rewards shareholders rather than hoarding excess cash.

The company's robust free cash flow (operating cash flow minus capital expenditures) exceeded $12.6 billion, powerfully demonstrating strong continuing cash generation capability even after funding substantial ongoing growth investments. This substantial FCF provides Walmart with strategic options including store expansion, e-commerce infrastructure development, and enhanced shareholder returns through dividends and potential buybacks.

Warning Signs: When Cash Flow Indicates Problems

Certain patterns in cash flow statements clearly signal emerging problems requiring immediate management attention and corrective action. Recognizing these red flags early enables intervention before situations become critical.

- Persistent Negative Operating Cash Flow over multiple consecutive quarters indicates fundamental business model problems. Short-term negative OCF during growth phases is normal. Extended negative OCF suggests the core business cannot sustain itself without continuous external financing.

- Declining Cash Conversion Cycles show deteriorating efficiency. When days sales outstanding increases, inventory turnover slows, or payables stretch excessively, working capital absorbs more cash.

- Heavy Dependence on Financing Cash Flow to fund operations signals distress. Healthy businesses fund operations and reasonable growth from operating cash flow. Continuous borrowing to cover operating shortfalls indicates serious problems.

- Negative Free Cash Flow Trends deserve scrutiny. Brief negative FCF during major expansion is acceptable. Sustained negative FCF suggests either excessive capital spending relative to business size or insufficient operating cash generation.

Conclusion: Using Cash Flow Analysis for Better Business Decisions

Cash flow analysis provides genuinely crucial insights that profit-based metrics consistently miss or obscure. Understanding what cash flow is and the three essential cash flow categories – operating, investing, and financing – enables substantially more informed decision-making about fundamental business health, promising investment opportunities, and optimal strategic direction.

The comprehensive regulatory framework established by FASB in 1987 ensures truly standardized reporting across all companies. This standardization, combined with sophisticated analysis ratios and rigorous valuation methodologies, meaningfully empowers both investors and managers to make genuinely data-driven decisions with greater confidence.

Whether you're carefully evaluating investment opportunities, actively managing a business, or systematically analyzing competitors, mastering cash flow analysis remains absolutely essential. The actual movement of real cash through a business reveals fundamental truths that accounting profits sometimes obscure or misrepresent.

FAQ

-

How often should businesses analyze cash flow?

Monthly cash flow analysis provides the optimal balance between actionable timeliness and reasonable effort for most established businesses. Weekly analysis makes strong sense for companies facing tight liquidity constraints or experiencing rapid growth. Quarterly analysis might suffice for very stable mature businesses with highly predictable patterns, though monthly remains preferable. During periods of significant change or uncertainty, even daily cash position monitoring becomes appropriate for maintaining financial control.

-

What industries typically have negative free cash flow?

Capital-intensive industries like telecommunications infrastructure, electric utilities, and heavy manufacturing often show extended periods of negative free cash flow during major expansion or modernization phases. High-growth technology companies building data centers might also show temporary negative free cash flow as they invest aggressively in infrastructure and market share capture before achieving profitability.

-

Can a company survive with negative operating cash flow?

Temporarily yes – if adequately funded by available investments or accessible financing sources. However, chronically negative operating cash flow signals fundamental business model problems requiring immediate comprehensive attention. No company can sustain normal operations indefinitely without eventually generating positive cash from core business activities. Even well-funded startups must demonstrate a credible path to positive OCF to maintain investor confidence and secure continued financing.

-

How do seasonal businesses manage cash flow?

Seasonal businesses require careful advance planning and adequate credit facilities. They build inventory and receivables during peak seasons, then collect cash during slower periods. Many maintain dedicated credit lines providing liquidity during seasonal troughs. Sophisticated seasonal businesses forecast cash needs annually, securing necessary financing before peak seasons begin. They also negotiate flexible payment terms with suppliers to align cash outflows with seasonal revenue patterns, smoothing the cash conversion cycle throughout the year.

-

What's the relationship between depreciation and cash flow?

Depreciation reduces reported net income without any corresponding cash outflow. The original equipment purchase consumed cash when initially acquired. Annual depreciation expense is simply an accounting allocation. When calculating operating cash flow using the indirect method, depreciation is added back to net income because it never involved cash.

-

How do investors use cash flow analysis?

Professional investors systematically examine cash flow patterns to rigorously assess business quality, earnings sustainability, and appropriate valuation levels. Strong, consistent operating cash flow indicates a fundamentally healthy business model. Substantial free cash flow drives sophisticated DCF valuation models and determines realistic dividend sustainability over extended periods.

-

What technology helps with cash flow management?

Modern cloud-based accounting systems provide real-time cash flow visibility. Specialized tools like Ramp, Daloopa, and various ERP systems automate transaction categorization, generate instant reports, and create forward-looking forecasts. These platforms integrate directly with bank accounts providing continuously updated cash positions.

-

How does cash flow analysis differ by company size?

Large public companies follow standardized FASB reporting requirements enabling direct comparisons. Small private businesses often use simplified cash flow tracking focusing on operating basics. Medium-sized companies typically adopt increasingly sophisticated approaches as complexity grows, often using professional accounting systems and periodic external analysis.